The State of Homelessness in America?

On Monday, the White House Council of Economic Advisors published a report titled “The State of Homelessness in America.” There is so much to talk about in this report that it would take more time than I can afford to write it, and it would be too long for you to want to read it. So, here is a summary of the report along with my commentary on the high points.

Report summary

Causes of homelessness

After describing the scope and variations in homelessness, the report identifies 4 key causes of the high rates of homelessness in the US:

- Overregulation of housing markets leads to higher housing cost which people with low incomes can’t afford, and thereby increase the number of people who are homelessness.

- Police policies that allow homeless people to stay and live on the street increase the number of people who are homeless. More tolerable conditions for sleeping on the streets (outside of shelter or housing) increases homelessness. However, some communities, including several in Florida and Arizona, experience considerably lower rates of homelessness than others with a similar climate, such as southern California. This suggests that other factors, for example “policies such as the extent of policing of street activities may play a role in these differences.”

- Increasing the number of beds in homeless shelters contributes to an increase in the number of people who are homeless. Cities with higher numbers of beds for homeless people, and in particular, those that have a right-to-shelter policy, have higher rates of homelessness, suggesting that “while shelter is an absolutely necessary safety net of last resort for some people, right-to-shelter policies may not be a cost-effective approach to ensuring people are housed.”

- “Severe mental illness, substance abuse problems, histories of incarceration, low incomes, and weak social connections each increase an individual’s risk of homelessness, and higher prevalence in the population of these factors may increase total homelessness.”

Previous failed policies

Next, the report assesses programs of previous administrations, particularly over the preceding decade, taking issue with permanent supportive housing (PSH) programs that adhere to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) guidance following the predominant evidence-based practice referred to as “Housing First.” Housing First emphasizes providing permanent housing without conditions. Supporting services, such as those for offender reentry, employment, physical health, mental health or addiction, are offered but not required. The report notes that:

“While these policies increase the demand for homes and thus reduce homelessness in the short-run, this short-run reduction can be reversed in the long-run through unintended consequences. In fact, it is not clear that this strategy has been successful in reducing homeless populations. Research suggests that previous Federal policy is not capable of explaining a substantial portion of the reported decline in homelessness between 2007 and 2018. In addition, we show that contrary to reported trends, it is unclear whether homelessness in the United States has actually decreased since 2007, due to an inconsistent definition of homelessness and miscounting of unsheltered homeless populations.”

Thus, the authors are not really sure if there was a decline in the homeless population over the last decade, but if there was, that does not mean that the Housing First evidence-based practice (EBP) is the cause. The report posits a few other possible alternative explanations.

The report goes on to say that the increase in beds for homeless people over the preceding decade has in fact increased the size of the homeless population. Using a simple economic model of supply and demand, the report notes that one factor “that explains variation in homelessness is the supply of substitutes to housing through homeless shelters. Expanding the supply of homeless shelters shifts the demand for homes inward and increases homelessness.” (Emphasis added.)

Policy recommendations

Having identified both root causes and failed policies, the report proceeds to make the following policy recommendations:

- Remove regulatory barriers to housing construction that would increase supply and lower cost. The report estimates that removing regulatory barriers to construction should decrease overall homelessness across the nation by 13% while some cities would see a much bigger reduction. The report estimates that San Francisco would see a reduction of 54% while Los Angeles would see 40% and New York would see 23% reductions. The report sites President Trump’s executive order of June 25 that establishes a White House Council on Eliminating Regulatory Barriers to Affordable Housing.

- Increase support for police efforts to remove homeless people from sleeping on the streets. “Another important factor that increases homelessness is the tolerability of sleeping on the street, which among other factors may be affected through policing of street activities. The administration has through a series of executive orders consistently supported the police.” The report does not suggest how or where people removed from the streets should be housed.

- To address contributing factors like addiction, offender reentry, mental illness and unemployment, the report cites the Administration’s efforts in each area without noting its proposed decreases in funding. “Strong economic growth, historically low unemployment rates, and reductions in poverty have increased the incomes of people at the bottom of the distribution and can reduce their likelihood of falling into homelessness.”

- Reform the Housing First model by imposing “service participation requirements for participants after they have been stabilized in housing,” and to “more quickly transition [people] to private housing,” thereby freeing up beds for others still living on the street. The report cites the 2019 HUD funding guidance that already implements these changes.

Beyond the estimated measures projecting the reduction in homelessness from removing regulatory barriers to housing construction, the report does not propose either goals or anticipated outcomes from the policies.

The report in context

We’d like to consider this report on its own merit, but as we are often reminded, context is… if not everything… then it is most certainly critical to understanding.

As reported by the media, we know that President Trump’s first priority is the effect of homeless people on the “prestige” of American cities not individual health, population health or the cost to society. “We can’t let Los Angeles, San Francisco and numerous other cities destroy themselves by allowing what’s happening. We have people living in our … best highways, our best streets, our best entrances to buildings and pay tremendous taxes, where people in those buildings pay tremendous taxes, where they went to those locations because of the prestige,” he said. “In many cases, they came from other countries, and they moved to Los Angeles or they moved to San Francisco because of the prestige of the city, and all of a sudden they have tents. Hundreds and hundreds of tents and people living at the entrance to their office building. And they want to leave.” (Washington Post, 2019)

Similarly access to homeless shelters is itself a topic of political contention. For example, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) regulatory agenda this fall includes a new rule which says shelters that receive, manage, or operate HUD grants can essentially ignore nondiscrimination protections for unhoused trans people. (Quinlan, 2019)

Reflecting these priorities, the broad policy direction from the Federal government for housing may best be reflected by the Administration’s proposed budget that reduces HUD’s funding by $9.6 billion over the next 10 years (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2019) and reduces funding for Medicaid by $1.5 trillion over 10 years. (Golshan, 2019)

In contrast, states, payers and private foundations are developing innovative funding and service delivery solutions that improve access to housing particularly in concert with supporting services. The report mentions a $1.5 billion bond issue that was passed in L.A. County in 2016 but it doesn’t mention the $2 billion program focused on housing and mental health that was approved by the people of California in 2018 which provides funding and services for every county in California, following the Housing First model. Other states are showing similar creativity and early success with the integration of housing and supporting services.

Nor does the report mention initiatives by payers such as Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest nonprofit, integrated health system, which, in May, announced $200 million investment to address the pressing social needs including housing, food, safety, utilities and more for millions of people across the United States through a comprehensive, far-reaching social health network to connect health care and social services providers. (Permanente, 2019)

The report also does not mention private foundations, like Jeff Bezos’ First Day Fund, which announced in November, 2018, that it was providing $97.5 million to 27 housing agencies. (Debter, 2018).

Beneath these conflicting policies is a raging political debate between liberals and conservatives over the role that government should play to support the most vulnerable people which will be at the fore during the run up to the 2020 presidential elections and will shape the direction of the US for years if not decades.

The scope of this discussion

In this discussion, we do not address many of the obvious questions that come out of this report. We do not evaluate the reasonableness of the very high estimated reduction in homelessness from reducing barriers to construction, or the possible damages or costs to society of abandoning these regulations. We do not question the expressed causal relationship between the supply of PSH beds and the rate of homelessness. We certainly do not delve into all the questions that arise from a policy of using the police to remove people from the streets and housing them in some un-named way other than PSH. We do not consider the impact of massive budget cuts on related services such as Medicaid, or the proposed reduction in Federal funding for housing itself. Finally, we do not consider the possible benefits to society if, through these policies, the number of people visible on the streets is reduced. While these are each important questions with complex answers, we believe the scope of this discussion gets at the heart of the matter for housing service providers, healthcare providers, Medicaid, Managed Care Organizations and policy makers.

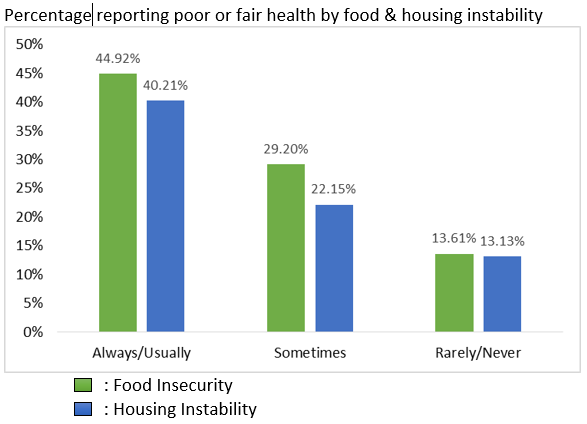

The association between housing and health status

It’s well established that there is a measurable association between housing and food insecurity and health status. As shown in our earlier study, Measuring the Association between Food/Housing Insecurity and Health Status: An Analysis using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, people who always or usually worry about having enough money for food or housing are about 3 times as likely to have self-reported poor or fair health compared to people who rarely or never worry, and are about twice as likely when compared to people who only sometimes worry about having enough money for food or housing.

Other than mentioning the Continuum of Care programs funded by HUD that expressly view housing in the context of other healthcare and social services programs, the report gives no consideration to the effect either of housing or housing programs on health status, outcomes or cost. This is a major omission in the overall policy discussion.

Housing First programs show mixed results—maybe.

The report notes that studies of the Housing First EBP show mixed results, with some showing considerable improvement in life satisfaction, lower cost or community wellbeing, while others show mixed or no improvement. The report makes general statements without presenting detail about whether or not health-related costs are considered in these analyses.

To our knowledge, the best literature review of studies relating to the effectiveness of PSH programs that follow the Housing First model, at least through the summer of 2018, was published by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine published in July, 2018 which “…found no substantial evidence that PSH contributes to improved health outcomes, notwithstanding the intuitive logic that it should do so…” (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2018) [Emphasis added.] Thus, the report is consistent with with the National Academies review.

However, that raises several questions. If the evidence does not show that PSH programs consistently contribute to improved health and social outcomes, does that mean that the underlying Housing First model is flawed and does not consistently achieve the stated results, or does it mean that the HF model is valid as an evidence-based practice but is not being consistently adhered to by PSH programs? Or does it mean, simply, that the wrong metrics are being tracked? Also, if policy makers, healthcare providers and payers, particularly Medicaid and its affiliated managed care organizations, see a trend towards a more fully integrated continuum of care, how does this trend look from the perspective of the PSH providers? Do housing service providers share the same view of an integrated continuum of care, with the same goals and coordinated EBP as healthcare providers and payers? And, finally, what role does technology play in achieving the goals of the integrated continuum of care at the intersection of housing and health?

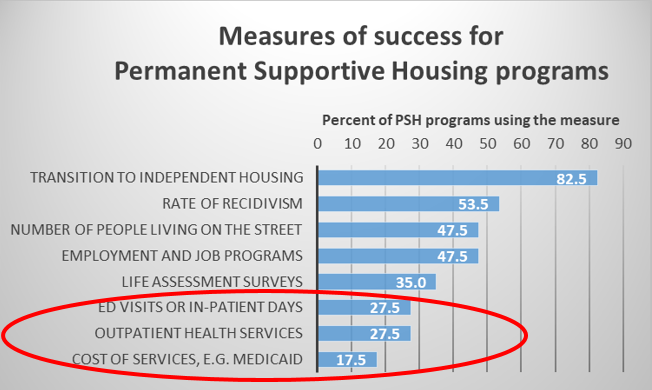

To begin to answer these questions, in April, we conducted a Survey of Evidence-based Practices and Technology Usage by Permanent Supportive Housing Programs. Among the questions we asked was What metrics do you track to measure outcomes (check all that apply?

As the graph shows, only a small percentage of PSH programs that follow the Housing First model even measure-health related outcomes or cost. This is consistent with the report’s observation that the present Housing First approach that makes supporting services available but does not require or even measure the effect on health outcomes or cost.

Our survey also showed that a similarly small percentage of PSH programs measure participation in supporting programs such as those for addiction, mental illness, chronic physical health conditions, employment or offender reentry.

Thus, the proposed policy change, to require residents in PSH programs to engage in supporting service activities as a condition of remaining in the housing program, is an interesting notion that imposes new duties and obligations on all stakeholders including social service providers and healthcare providers as well as clients. As important, this policy shift may provide incentives and funding for research into the effectiveness of variations on the Housing First theme. These could be of tremendous value not only in the near term but over the long term, regardless of who is in the White House.

Implications for stakeholders?

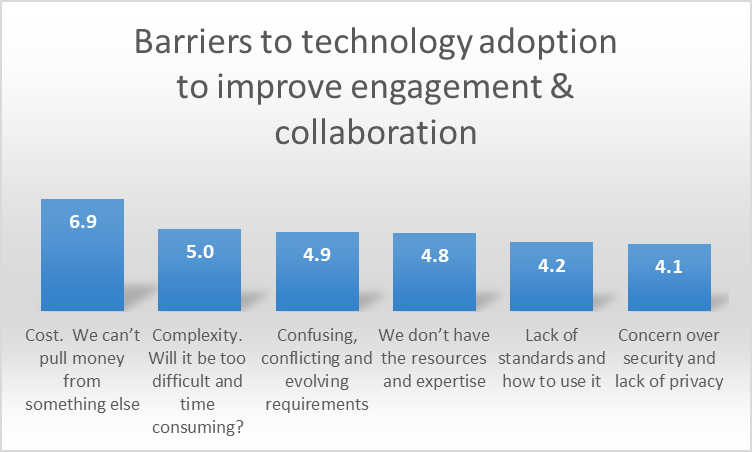

As noted in the report, and as is common knowledge, many of the Trump Administration’s policies are implemented through executive order or department regulation rather than through Congressional legislation. That means they may be subject to amendment or repeal by subsequent administrations without involving Congress. This insecurity, combined with the inherent complexities of client engagement and care collaboration exacerbate the barriers PSH providers see to adopting innovative workflows and technologies.

As we learned in our survey, PSH programs perceive cost, complexity, confusing/conflicting/evolving requirements and limited expertise as the primary barriers to technology and workflow innovation.

Thus, all stakeholders, including PSH programs, social service providers, healthcare providers and managed care organizations, will face considerable challenges as the details of these policies are announced.

Furthermore, the shift in emphasis from permanent housing supports to minimizing the duration in supported housing may be inconsistent with the goal of improving collaboration across the continuum of care. If the goal is to improve health and life style behaviors for those in housing programs, can that goal be met while simultaneously seeking to move people out of the program as quickly as possible? These are tremendous opportunities for innovation, research and leadership.

Conclusions

Overall, we come away from the report with a clear sense that the foundational purpose of the recommendations is to improve the appearance of the American landscape with a secondary focus on improving individual lives, population health or reducing total cost. That in itself is problematic.

Some of the recommendations, when considered in light of other policies are also problematic. What is the real-world impact of eliminating barriers to construction? What will be the larger consequences of a program to reduce homelessness through police enforcement? Will reducing the supply of and funding for housing itself have the posited effect of reducing homelessness? Can the Federal government increase its focus on mental health, addiction and employment while at the same time slashing budgets for those programs? These are just some of the challenging questions that will be subjects of much debate and may take years to sort out.

On the other hand, the proposal to reform the Housing First model by increasing the linkage between housing services and supporting services may have merit. It is not simply a step back to the pre-Housing First days when housing was considered to be a reward for participation in services, a model which failed. Reforms that promote and improve an integrated continuum of care are less likely to be undone should a liberal administration come into office in 2021. Indeed, it is reasonable to expect that Democratic policies might not just continue such programs but might extend programs that promote an integrated continuum of care.

While we can’t embrace all the provisions of the report, those provisions that recommend reforming the Housing First model confirm what we have been saying all along: the only way to achieve our national objectives, including improving individual and population health, lowering cost, improving care giver experience and even improving the appearance of our society, is by promoting a truly integrated continuum of care, regardless of which administration is in power.

Next steps

The 2019 funding guidance for HUD has already been published, encouraging communities to require people in housing programs to engage in supporting services programs for addiction, mental illness, chronic physical health conditions, offender reentry and employment. So we’re not waiting for something new to come out.

In order to make the most of this opportunity, we propose the following:

- The Federal government and states must continue to improve revenue models for every stakeholder, to ensure continuity and sustainability for the long term.

- Payers, particularly managed care organizations, must show leadership to drive these changes. Policy and technology can only go so far. Leadership from payers is the lynchpin to achieving the quadruple aim: improve individual health, improve population health, reduce total cost and improve provider satisfaction.

- Technology vendors must follow innovation in other industries to deploy new solutions that are low cost, easy to use, and incredibly flexible to meet these evolving requirements without the high cost of consulting and programming services. White Pine’s patent-pending proVizor Care Collaboration Platform is the ideal platform.

- Communities, including housing providers, other SDOH providers, healthcare providers, recovery and offender reentry specialists and managed care organizations need to immediately engage in collaborative discussions about evidence-based practices, goals, metrics, workflow and technology.

Join the proVizor Community. Help us shape your future.